Hockey and Physics

Physics is present in all aspects of hockey, from skating and stopping to passing and shooting.In hockey, a player's skates serve two purposes; the skates' edge can push off the ice when needed, creating speed, and, once this force has been applied, the design of the blade allows the skate to glide over the ice. The blade also enables the player to change direction quickly, whether that be turning or stopping. With that being said, the actual playing surface of hockey, the ice, is what enables many of the things that occur in a game of hockey that would be otherwise impossible on a playing surface such as turf, grass, or dirt. This is because of the low friction of the ice, as well as its softness, which allows the skate blade to dig in, creating more force. There are also different types of sharpenings that a player can get for his or her skates, which result in more or less bite by the blade and thus enable more or less push by the skater.

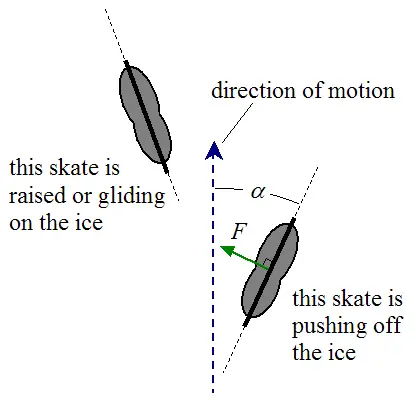

The speed at which a player skates is affected by the force that they are able to generate with their legs in their push off the ice, as well as the angle at which this force is created in regards to the y axis. The greater the angle that a player is able to position their feet when skating creates more force in the forward direction and makes them go faster.

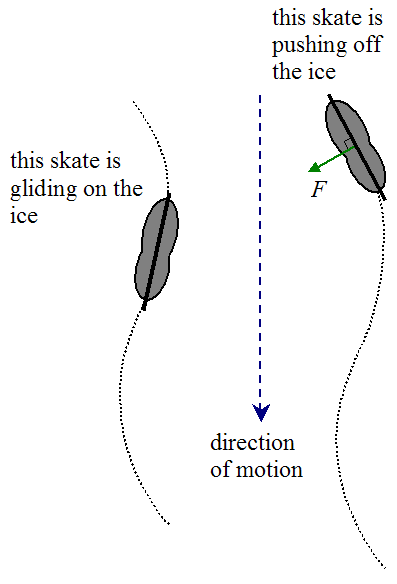

In comparison, when skating backwards, the physics concerning how fast a player can move is a little different. When skating backwards, a player moves his or her skates in a path that creates an "S" (most coaches describe this way of skating as "c cuts"). When skating backwards, the player cannot push off the ice with the same type of force that he or she would be able to when skating forward. This is because, unlike when one is skating forward, the players skates never leave the ice.

In comparison, when skating backwards, the physics concerning how fast a player can move is a little different. When skating backwards, a player moves his or her skates in a path that creates an "S" (most coaches describe this way of skating as "c cuts"). When skating backwards, the player cannot push off the ice with the same type of force that he or she would be able to when skating forward. This is because, unlike when one is skating forward, the players skates never leave the ice.The skate also plays a big role in stopping and turning. The ability to change directions quickly in hockey is crucial, so players seek to find the right balance between skating fast and being able to "stop on a dime". This relationship between the speed at which the player is skating and the time that it takes them to stop can be simply represented by the equation delta(x)=vt. There is one catch, however. Due to the nature of the ice and skate blades, skate blades must be sharpened regularly if a player wishes to stop as quickly as possible. Otherwise, the blade is dull and just slides over the ice.

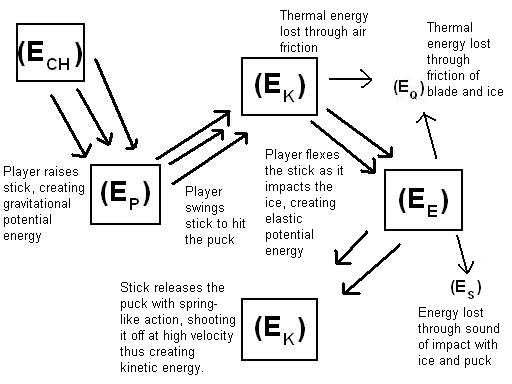

Another part of hockey that can be evaluated using physics is shooting the puck. When shooting a puck, a player must apply more force on the puck than the amount of force resisting the puck's movement, which is friction. However, because ice has very little friction, players are able to send the puck flying through the air at very fast speeds. The energy involved in a hockey shot is shown below. Additionally, a major part of players being able to create such force is the design of hockey sticks. Hockey sticks are made of fiberglass, which is a material that is able to withstand tremendous stress by flexing. Players use this flex to their advantage. By applying force on the ice behind the puck, players are able to build up energy in their stick like a spring, and then, when they release this pressure, all of this stored energy is transferred towards the puck.

Another part of hockey that can be evaluated using physics is shooting the puck. When shooting a puck, a player must apply more force on the puck than the amount of force resisting the puck's movement, which is friction. However, because ice has very little friction, players are able to send the puck flying through the air at very fast speeds. The energy involved in a hockey shot is shown below. Additionally, a major part of players being able to create such force is the design of hockey sticks. Hockey sticks are made of fiberglass, which is a material that is able to withstand tremendous stress by flexing. Players use this flex to their advantage. By applying force on the ice behind the puck, players are able to build up energy in their stick like a spring, and then, when they release this pressure, all of this stored energy is transferred towards the puck.

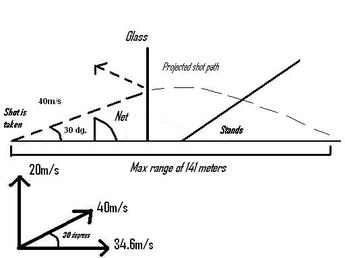

Also, players are able to elevate the puck due to the construction of the stick blade. A hockey stick blade is tapered slightly up so that when a player shoots a puck, the puck slides

down the blade and is lifted off the ice. The angle at which the puck leaves the ice also affects its velocity and overall trajectory. Although the puck is usually stopped from reaching its total possible trajectory by the goalie, the net, or the boards, its motion through the air can be represented by projectile motion. As such, the maximum distance and height of a shot can be established using kinematic equations.

Lastly, torque and impulse are crucial to passing the puck in hockey. Impulse equals momentum divided by time, and, as such, it can be effected by the velocity of the pass and the time it takes the puck to travel from one stick to another. Knowing what impulse is and the factors involved is important to hockey because a player wants to have enough impulse so that the puck is traveling at a relatively fast speed and cannot be intercepted by the opposing team, but not too much impulse that a teammate cannot catch the pass. Furthermore, knowing that torque equals the radius (in this case from the heel of the stick blade) times the force applied to the puck and the sine of the angle between the radius and the force, is important because it helps you understand where the best place to catch a pass is. The greater the torque, the harder it is to maintain control of the puck. With that being said, a player can increase his or her chances of receiving a pass without error by receiving the pass on the heel of the stick rather than the toe.

Works Cited

“Physics Of Hockey.” Real World Physics Problems, www.real-world-physics-problems.com/physics-of-hockey.html.

Comments

Post a Comment